Iron for the Young Athlete

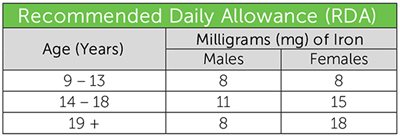

How much iron do children and teens need?

There are daily recommended amounts of iron based on age and gender. Athletes and active individuals may need more than the recommended daily allowance.

What is iron deficiency?

Iron depletion or deficiency occurs when the body does not have enough iron because of:

- poor iron absorption.

- excessive iron losses.

- low iron intake.

How can iron deficiency affect young athletes?

Low iron and iron deficiency both impair the blood’s ability to carry oxygen to body tissues, including the heart, lungs, and muscles. This can cause fatigue, shortness of breath, and many other symptoms. A young athlete with low iron will often feel tired and burn out early in practices, games, and meets, which can lead to decreased performance and possible injury.

”While risk of iron deficiency is higher in vegetarian athletes and female athletes, these are not the only individuals at risk,” says Taylor Morrison, M.S., R.D.N., CSSD, L.D. “Distance runners, those training at altitude, those going through rapid periods of growth, and those who are underfueling, or not consuming enough total calories and iron-rich foods, are most at risk for iron deficiency.”

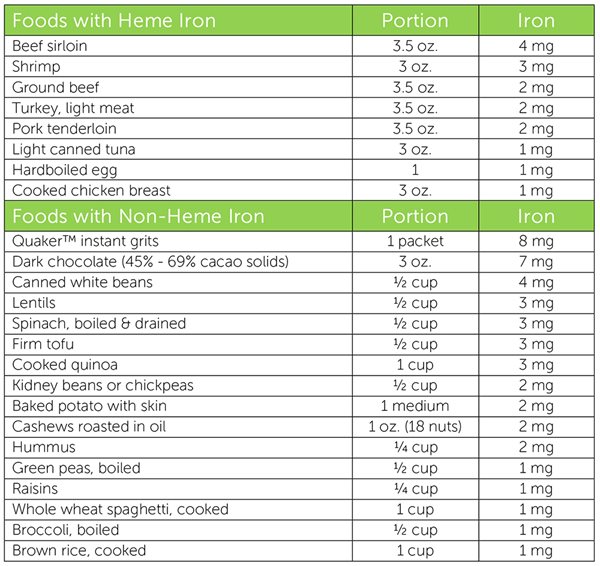

What are the sources of iron in the diet?

There are two forms of iron.

Heme iron is found in animal sources and is more efficiently absorbed in the body than non-heme iron.

Non-heme iron is found in plants. Individuals that follow a vegetarian eating plan can still meet iron needs through non-heme food sources if they are intentional.

What affects iron absorption?

Factors That Reduce Iron Absorption

- Compounds called phytates and oxalates are found in many plant-based foods.

- Tannins found in tea and coffee

- Calcium and excessive intake of zinc and manganese

Suggestions to Improve Iron Absorption

- Add foods containing vitamin C to meals with non-heme sources.

- Sources include citrus fruits, strawberries, kiwi, bell peppers, tomatoes, cauliflower, broccoli, melon, and mango.

- Eating heme sources of iron with non-heme sources.

- Drink tea or coffee separately from an iron-containing meal or snack.

- Cooking in a cast-iron skillet.

- Add allium plant herbs like onion and garlic to your iron sources.

Examples of Meals and Snacks That Improve Iron Absorption

- Spinach salad topped with sliced strawberries.

- Steamed broccoli with lemon juice squeezed on top.

- Trail mix includes an iron-fortified cereal and raisins with a glass of orange juice.

- Cooked whole-wheat spaghetti with marinara sauce and fresh tomatoes topped with grilled shrimp and broccoli.

- Black bean, quinoa, and mango salad.

- Raw bell pepper slices, cauliflower florets, and grape tomatoes with hummus.

If you are worried your athlete is struggling with iron depletion or deficiency, visit with your doctor and a registered sports dietitian to see if dietary changes or supplementation are needed.