As a pediatric orthopedic surgeon,

Corey S. Gill, M.D., M.A., cares for many children with DDH and has received several questions from referring providers about appropriate care. The most important things for pediatricians and other referring providers to understand about DDH include:

- Perform a hip examination on every newborn and infant patient. Soft tissue clicks around the hip and knee are very common and do not generally indicate hip dysplasia. Similarly, asymmetric skin creases on the inner thigh do not usually mean there is a problem with the hip. Findings that are clearly abnormal and should lead to orthopedic referral include:

- An unstable hip that “clunks” into or out of place. Hip stability is evaluated during the exam by performing the Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers. The Barlow test identifies a hip that is in place but can be easily dislocated with gentle pressure. The Ortolani test identifies a hip that is dislocated at rest, but can be placed back into the joint with positioning of the thigh.

- Significantly decreased or asymmetric range of motion. This is especially important for abduction of the hips, which is moving the hips out to the side when lying down. Differences as small as 10 degrees compared to the normal side may indicate a significant problem.

- A significant leg length difference, which may indicate a hip dislocation. Leg length difference is best evaluated with a Galeazzi test. This test is performed by flexing the hips to 90 degrees and checking to see if the knees are level.

- In toddlers and older children, decreased hip abduction and a waddling gait, limp or unilateral toe walking may indicate hip dysplasia or dislocation.

- Identify the risk factors that make hip dysplasia more likely. The two most important are family history of hip dysplasia and breech presentation (especially frank breech). Providers should have a low threshold for orthopedic referral in these patients. Other risk factors include female sex, first born child and oligohydramnios.

- Understand the right time to refer a patient for DDH evaluation. In newborns with unstable hips on exam, a referral should be made immediately so treatment can start as soon as possible. In children with a normal exam but risk factors for DDH, an ultrasound should be obtained at approximately six weeks of age. Obtaining an ultrasound in children earlier than this often leads to a false positive diagnosis of DDH secondary to physiologic immaturity of the hip joint in the newborn.

Orthopedic Intervention

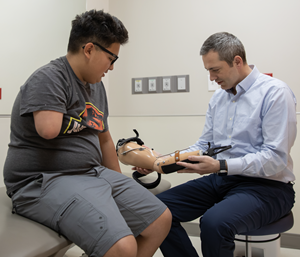

When infants do need orthopedic intervention for hip dysplasia, our first line of treatment is a Pavlik harness. This fabric and Velcro harness is generally worn for 23 hours per day for approximately six to eight weeks, but it is removable for bathing. The harness keeps the hips flexed and rotated in the correct position for normal development of the hip joint. After treatment with a Pavlik harness, we use physical exams, ultrasound and X-rays to monitor growth and confirm the hip joint is developing normally. Most infants with DDH require no further orthopedic treatment after wearing a Pavlik harness.

In some infants, especially those with severe hip dysplasia or a dislocation, Pavlik harness treatment may not be successful. Occasionally, a different type of hard plastic brace may be successful in correcting the hip dysplasia in these children. However, most children who do not respond to Pavlik harness treatment will ultimately require surgical intervention to prevent long term problems from hip dysplasia such as cartilage injury, limp, leg length difference and early arthritis. Depending on the severity of the hip dysplasia, surgical treatments may include:

- Closed reduction – This involves repositioning the ball of the hip joint deeply into the socket when the child is asleep under anesthesia and then applying a body cast called a spica cast for a total of three to four months. During this procedure, we often inject a small amount of medical dye into the hip joint to confirm that the ball of the hip joint is appropriately positioned in the socket. This is called an arthrogram.

- Open reduction – Sometimes the hip joint will not line up well with repositioning of the leg because there are tight tissues blocking the ball from sitting deeply in the socket. In these cases, an incision is made in front of the hip where the tight tendons, ligaments and soft tissues are moved out of the way. Afterwards, the lining of the hip joint is tightened with a strong suture to help hold the hip in position. This procedure is called a capsulorrhaphy.

- Osteotomies – In older children (over age 1.5 – 2 years), soft tissue procedures alone are often not enough to ensure the hip joint is lined up well. In these cases, we often supplement the open reduction procedure by cutting the bone in a controlled way to help reorient the hip into the socket. This is called an osteotomy and can be performed on the ball side of the hip (femur osteotomy) or socket side of the hip (pelvic osteotomy). Metal implants are often used to hold the bone in the new position and are removed at a later date.

Conclusion

Hip dysplasia is a common orthopedic condition in newborns that can lead to significant long-term consequences if left untreated. Certain risk factors such as family history of dysplasia and frank breech presentation greatly increase the risk of developing DDH. Pediatricians play a crucial role in examining infants, identifying those with risk factors and referring them to a pediatric orthopedic specialist when appropriate. When diagnosed in the first few months of life, noninvasive treatment with a harness or brace is highly successful and generally leads to the development of a normal hip. In some cases of severe hip dysplasia/dislocation or in cases of delayed diagnosis, surgical intervention is required to improve the long term prognosis of the hip joint.

Referral Tips

A potential diagnosis of hip dysplasia can lead to significant anxiety for new parents. Understanding the best time to refer patients and initiate treatment helps to maximize treatment success and efficiency while minimizing parental stress and worry.

- For infants with risk factors for DDH such as family history or breech presentation but a normal physical exam, an ultrasound should be obtained around six weeks of age. Ultrasounds performed earlier than this age result in a large number of false positives and potential unnecessary treatment in a harness.

- There is no need to obtain an ultrasound prior to referral as we work closely with experienced ultrasound technologists who can perform the diagnostic hip ultrasound on the same day as an infant’s office visit.

- In children with a clearly abnormal exam (unstable/dislocatable hip or asymmetric hip abduction) in the nursery or in routine office visits, immediate referral should be made so that treatment in a harness can be initiated as soon as possible. In these children, there is no need to wait until the child is 6 weeks of age for referral.

- If only abnormal exam finding is a “hip click” or asymmetric thigh crease, referral and ultrasound should be deferred until 6 weeks of age given the relatively low prevalence of DDH in these children.

- In premature infants still in the NICU with risk factors for DDH, it is generally OK to wait for referral until after the child is discharged to go home. If an examiner finds the hip to be unstable while still an inpatient, phone consultation with a pediatric orthopedic surgeon is available to answer questions or discuss the most appropriate time to see the patient.

- If a family has an infant diagnosed with DDH, all future siblings of the child should be referred for screening, ultrasound at six weeks of age and strong consideration should be given for referral of older siblings for a hip radiograph. First degree relatives have more than a tenfold higher risk of DDH compared to controls.

/Ann,-Hip.jpg?width=400&height=266)