Fifty years ago, a man with an unwavering conviction to help children joined Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children’s staff. His name was Lucius “Luke” Waites, Jr., M.D., and his pioneering work changed the world of learning disorders forever.

In 1924, Lucius Waites, Jr. was born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, during a formative time in the study of learning disorders, such as dyslexia. The condition is characterized by a difficulty connecting letter symbols to sounds. It makes reading challenging and affects roughly 10 percent of all public school children.

For a child with dyslexia, the world can be a daunting place. Feelings of failure or isolation can often accompany the condition. Little did anyone know that one day Waites would not only study dyslexia, but he would also help define it and ultimately change perceptions, treatment approaches, education, legislation and the lives of countless children in the process.

While playing football for Ole Miss, Waites gained a reputation for being a fierce competitor, playing in the era of no protective facemasks. That fearless spirit and drive to succeed would serve him well throughout his career. He graduated from the University of Tennessee College of Medicine in 1947 and began his work as a neurologist. He came to Dallas in 1961 to join the faculty at UT Southwestern Medical Center. From 1961-65, he also assisted the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children medical staff in the area of neurology.

During that period, Waites began to investigate the phenomenon of smart children who struggled to read. This condition was initially described as “word blindness” and “twisted symbols” (aka: Strephosymbolia). Research into this condition was considered fringe medicine at the time and often mocked as “quackery,” but the determined football player from Mississippi refused to give up. Then Scottish Rite Hospital Chief of Staff Brandon Carrell, M.D., observed the positive effect Waites’ methods were having on his patients and stood by his efforts. In 1965, Waites moved to Scottish Rite Hospital full time and the Luke Waites Center for Dyslexia & Learning Disorders was born. With the support of Scottish Rite Hospital and the Masonic community, Waites set out to build a program dedicated to diagnosing and treating children with the condition. Along with language therapist Aylett Royall Cox, Waites developed the hospital’s first dyslexia curriculum called Alphabetic Phonics. This new approach, with its dramatic and positive results, made waves in Dallas, across Texas and beyond.

“The support of the hospital, the administration and the board of trustees continues to be strong and crucial to our work,” says Gladys Kolenovsky, the center’s administrative director and a 39-year staff member. “From the beginning, they believed in what this center could do for children.”

In 1968, Waites organized a meeting of the World Federation of Neurology at the hospital, at which the medical term “developmental dyslexia” was defined. For the first time, dyslexia was recognized as a medical condition that called for an educational treatment.

But Waites did not stop there. In 1985, he enlisted the help of two equally tenacious colleagues — Kolenovsky and Geraldine “Tincy” Miller, a former staff member who has gone on to serve more than 26 years on the Texas State Board of Education. Together, they facilitated two major changes in Texas education laws — separating dyslexia from special education programs and requiring dyslexia screening and testing in all public schools. As a result of their efforts, Texas became a leader in public policy for learning disorders.

“Because of this incredible group of individuals who were willing to take a chance, so many people are able to stand on the shoulders of their legacy and their bravery,” says Karen Avrit, the center’s educational director, who recently helped pass House Bill 866. This bill ensures that all undergraduate education majors in Texas learn how to recognize, identify and make basic accommodations for children in their classrooms who may be dyslexic.

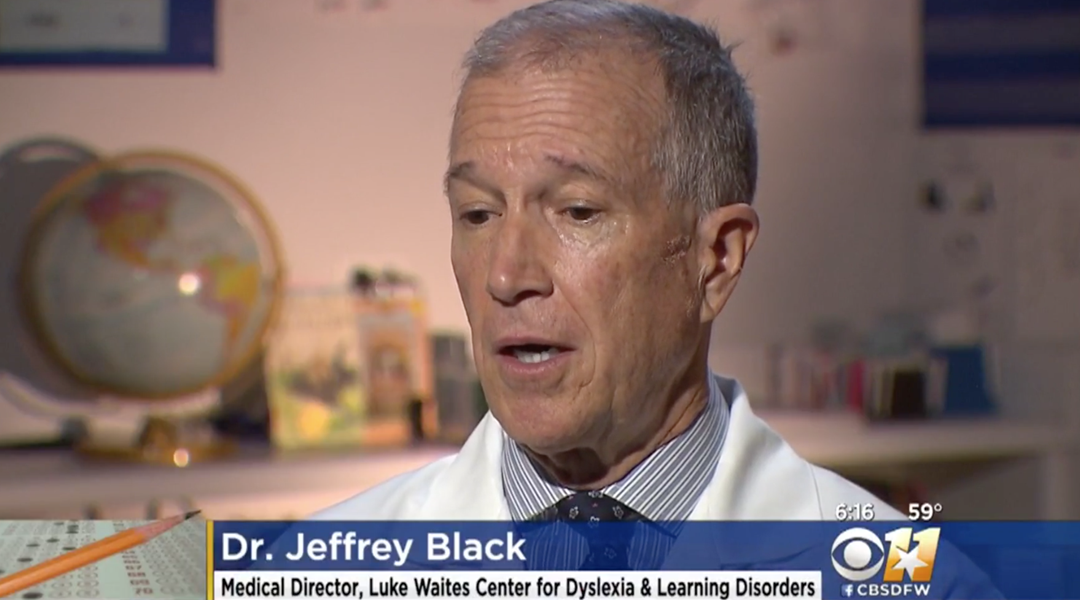

In 1990, Jeffrey Black, M.D., joined the Scottish Rite Hospital medical staff and the crusade, alongside Waites. Where Waites drew from clinical knowledge and child-focused intuition, Black revels in the scientific process. He set a high bar for data collection, results-driven experimentation and extensive research.

Black used precise, quantifiable measurements to prove that dyslexia could be remediated. From there, he proceeded to improve and adjust the existing curriculum based on his findings. It was through his unflinching dedication to data analysis that a new curriculum, Take Flight: A Comprehensive Intervention for Students with Dyslexia, was developed.

The curriculum allows children to learn the course material faster, with a higher retention rate. The first edition was printed in 2006. Today, Take Flight is used across America, in Canada and as far away as Dubai. The morning Avrit got a call from the Middle East inquiring about the program, she recalls saying, “Wow, we’ve gone international!”

The future of Take Flight looks bright, as Black and the team embark on the next journey in dyslexia education. Together with The University of Texas at Dallas, they are taking the curriculum into the digital arena. Through interactive technology, they will share the program with the next generation of children as well as increase its reach and scope for teachers.

Black is also pushing dyslexia research into the world of genetics. In collaboration with Jerry Ring, Ph.D., the center’s research scientist, and Scottish Rite Hospital’s remarkable genetics research team, work is being conducted to better understand dyslexia on a genetic level.

In 2013, the strong-willed Waites passed away at the age of 89, leaving behind a legacy that has changed the lives of individuals with dyslexia forever.

“It is wonderful to recognize Luke Waite’s legacy, while also paying tribute to the core values of the dyslexia department and the hospital,” Kolenovsky says. “The child comes first – always.”

**This article appeared on the cover of our Rite Up 2015: Issue 3 magazine. Read more from the magazine online.