Bouncing Back From UCL Injury Scarlette Soars Higher Than Ever

Published in Rite Up, 2023 – Issue 3.

by Kristi Shewmaker

It was a nail-biting week for Scarlette, of Coppell, during the fall semester of her high school senior year. She was waiting for a phone call from the head coach of the gymnastics team at Rutgers®. She hoped the coach would invite her to join the team. Years before, she had set her sights on going to Rutgers and competing there as a gymnast.

In competitive gymnastics, recruitment for joining a college team begins around an athlete’s sophomore year of high school. During that time, Scarlette visited the campus, attended gymnastics camps and participated in an official visit to get to know the coaches and student gymnasts. All that was left for her to do was wait for “the call” to let her know if her college dreams were coming true.

Born and raised in Oahu, Hawaii, Scarlette started gymnastics when she was 4. “She had tons of energy in preschool,” says Bryan, her father. “She was always hanging from the monkey bars and bouncing around.” Her parents enrolled her in a recreational gymnastics class to burn off energy. “We knew nothing about the sport, apart from what we saw in the Olympics,” Bryan says. But, the coaches picked up on Scarlette’s innate ability, and she excelled quickly. At her first gym, they suggested that she try out for a team. “That was the start of my gymnastics career,” Scarlette says. “I was 6 or 7 years old in my first competition.” And in that early competition, she won. Throughout the years, Scarlette kept winning.

By the age of 14, she rapidly advanced to level 10, the highest level in the USA Gymnastics Development Program. During her first year as a level 10, she made it to the national competition in Indiana, an incredible feat for her age. To ensure that Scarlette and her younger sister, who is also a gymnast, could get exposure and compete in bigger, more prestigious tournaments on the mainland, the family packed up and moved to Texas, specifically for the program at Texas Dreams Gymnastics in Coppell.

During her sophomore year, Scarlette tripped as she was running into a tumbling pass and rolled her ankle, landing on her arm. “In Hawaii, we have several hospitals but only one main hospital for children,” Bryan says. “In Texas, we didn’t know where to go, but her coaches and other gymnasts’ parents said, ‘You have to go to Scottish Rite for Children.’” At Scottish Rite for Children Orthopedic and Sports Medicine Center in Frisco, Scarlette learned that she had not only sprained her ankle but also would need care for a more complex injury to her ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) in her left elbow. Assistant Chief of Staff and Director of the Center for Excellence in Sports Medicine Philip L. Wilson, M.D., evaluated Scarlette and consulted with her and her family regarding her individualized treatment options.

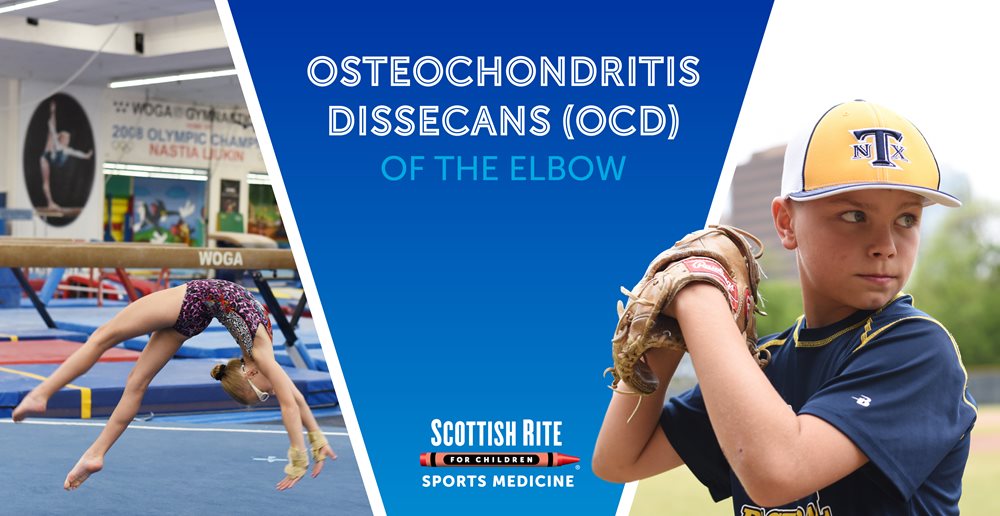

The UCL is a band of tissue that runs along the inside of the elbow and works to stabilize the elbow joint during overhead movements. Baseball players, gymnasts and, occasionally, quarterbacks sustain this injury. “It has to do with the way you use your elbow, either for weightbearing or throwing,” Dr. Wilson says. Baseball players sustain the injury from repetitive throwing, bringing the elbow back at a certain angle repeatedly, causing stress on the ligament. “For gymnasts, it’s a weightbearing issue,” Dr. Wilson says. “We all have a little bit of an angle in our elbow called valgus. Gymnasts develop more of that angle as they grow due to repetitive weightbearing from a young age.” The force of a gymnast landing on her hands over and over causes repetitive stress on the ligament.

For most people, the treatment plan for a UCL injury is nonoperative with a recommendation of rest and physical therapy (PT). For athletes like baseball players or gymnasts, the plan could include surgery, depending on their injuries and their goals. “When we consulted with Dr. Wilson, part of Scarlette’s treatment plan depended on whether she wanted to stay at the competitive level or just do gymnastics for fun,” Bryan says. The direction she chose would determine the aggressiveness of the treatment.

“It is always challenging for the family to make a decision about what to do,” Dr. Wilson says. Ligament reconstruction surgery requires a long commitment to rehabilitation, and often takes a year for the athlete to get back to the competitive level. “An important part of our job is to partner with the family, provide quality counseling time and ensure that they have all of the information they need to make the best decision,” he says.

In their initial consultation, Bryan said that it was the first time he heard Scarlette say that she wanted to do gymnastics just to enjoy it. “A few months before my UCL injury, I had been struggling a lot in the gym,” Scarlette says, “and when I got hurt, I was like, ‘Is this a sign? Is this telling me to just be done?’” Bryan explained that Scarlette had hit a plateau in her skillset, which is common for competitive gymnasts, and in her mind, the injury was a setback.

Scarlette decided to take the nonoperative route, and Dr. Wilson recommended PT twice a week at Scottish Rite. After seven months, Scarlette was back in the gym when she injured her elbow again. “I was doing a release on the uneven bars, but I missed the bar and landed on my hands and knees,” she says. “The pain shot up my whole arm.”

After the reinjury, Scarlette decided to pursue surgery. “I was getting my skills back, and I think I just needed to take a step back and rest my body,” she says. “I was able to think.” The light at the end of the tunnel, Bryan said, was that she would get a new ligament in her elbow, and she would be much stronger.

Scarlette underwent surgery the summer before her junior year. Wearing a brace, she started range of motion exercises and began PT within the first week. Over many months, her therapy goals included regaining mobility of her joint and then progressing toward strengthening, endurance and power production. At six months, she went back to the gym while continuing PT, and at eight months, she resumed training but not at full skill level. Finally, the summer before her senior year, she was given the all clear to train without restriction and to fully return to gymnastics that fall.

“I learned a lot about myself during my recovery,” Scarlette says. “I had to build my way back up. The basics I received to get my skills back really helped my confidence and my performance. I trusted my care team, their process and everything they did.”

“I have massive respect for the program at Scottish Rite,” Bryan says. “Dr. Wilson gave Scarlette the option to do what she wanted to do. He didn’t go right to surgery. The professionalism of him to offer PT first, that he even took that into consideration, is a big deal. For any parent considering a facility for their child’s orthopedic needs, it’s a no-brainer. There’s no reason to go anywhere else.”

In the 2023 gymnastics season, Scarlette finally got to compete in all four events — vault, uneven bars, balance beam and floor exercise. “After all that she had been through, it was enlightening to see her compete,” Bryan says. “Her demeanor changed. She was driven and confident, not too deep in thought. She just went out there and did her thing, and let it be in the judges’ hands.”

After more than a year and a half of injuries, surgery and recovery, Scarlette said that waiting to hear from Rutgers felt like forever. But, the phone finally rang. She was officially offered a position on the team. And, her answer was, of course, yes!

“I’m excited for a whole new chapter,” Scarlette says. “I get to experience college life as a student athlete and compete on a much bigger stage. I can’t wait to experience that whole new world!”