By Marin Wolf

Read the full article.

Dwight Putnam spends a lot of time looking at the ground. It’s a habit he picked up as an artist, always searching for shards of glass and metal for industrial sculptures that were crafted to make people appreciate the beauty in the mundane.

For nearly a decade, the North Texas native hid tiny pieces of everyday life in his art. Now, Putnam, 51, does the opposite. As a prosthetist at the Scottish Rite for Children orthopedic hospital, he creates functional pieces of art that enhance the lives of pediatric patients who are missing limbs.

Putnam’s office and work space in the Dallas hospital’s lower floor is reminiscent of an art studio, but with medical-grade equipment and special technology that helps him visualize the artificial arms and legs he makes. He and his team of prosthetists and orthotists craft more than 300 limbs a year, each tailored to the needs of individual patients.

“I don’t do too much sculpting these days. Making arms and legs fills that artistic need,” Putnam said. “Watching these patients, it helps you keep your own life in check.”

Most of the practitioners at the orthotics and prosthetics department work with both types of devices, creating orthotics to help brace existing limbs and prosthetics to replace missing body parts. Putnam is one of the few who works only in prosthetics, and although he specializes in upper-extremity devices, he works with patients missing lower limbs as well.

Putnam spends each day designing and revising multithousand dollar devices that give children the opportunity to fully participate in sports, music and even simple activities, like walking with their friends between classes.

Two of his creations belong to 10-year-old Elena Norman, a fifth grader from Temple who had her leg amputated above the knee at Scottish Rite when she was a toddler because it couldn’t straighten and hindered her ability to walk. It was a difficult decision, her mom, Brittany, said, but she can do almost anything that children without prosthetics can do.

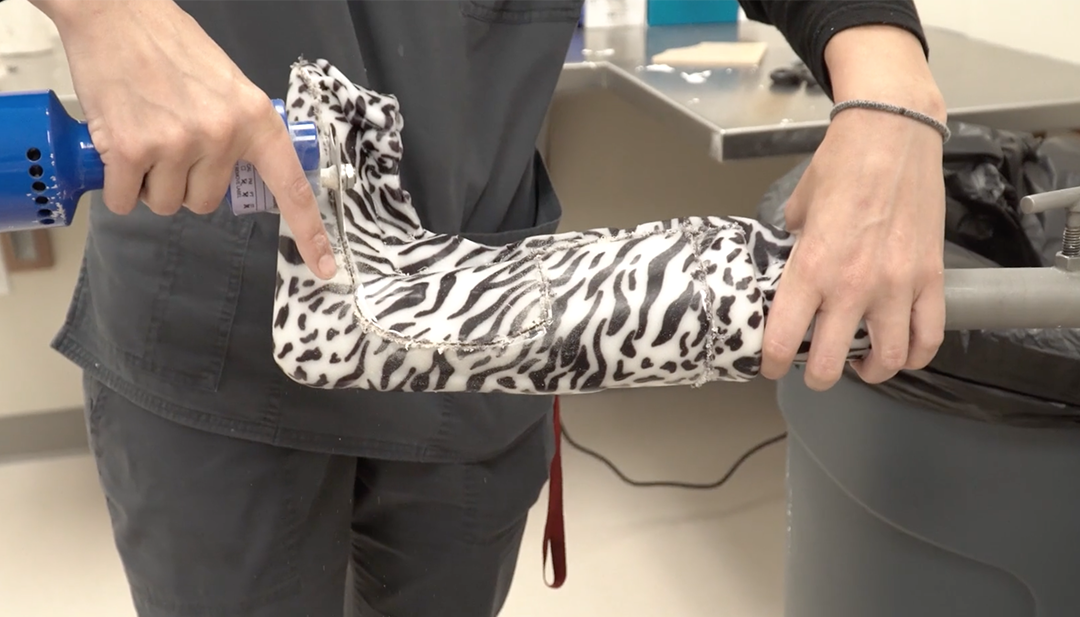

She spends most of her time on her blue and green leopard print “daily” leg, but switches to her “sport” leg when she’s running on the beach, tumbling in gymnastics or walking miles around a theme park.

“I definitely know it’s there, but it’s my normal,” said Elena, who also sees some of Putnam’s colleagues to treat her scoliosis. “I don’t think about it that much. It’s kind of just a part of me.”

Despite the central role his artwork plays in his patients’ wellbeing, Putnam is happy to sit on the sidelines.

“These kids are so resilient. It’s all them,” he said. “I consider myself their pit crew while they’re out there running the race of life.”

–Lending a helping hand

Putnum, who grew up in Carrollton, thought he wanted to be a doctor when he was an undergraduate student at Austin College. After one organic chemistry lecture, however, he decided to switch paths.

He became one of two art majors in his graduating class and soon found work in commercial sculpting. He made art installations for casinos, event centers and zoos while continuing to make abstract sculptures out of concrete and rusted metal.

Putnam said he loved his job and that he got to work with his hands. But after a few years, the inconsistent industry started to take a toll.

“It’s very much feast or famine,” he said.

In a lull between sculpting gigs in the early 2000s, the artist applied for a job making silicone body parts for Life-Like Laboratory, a silicone prosthesis business in Carrollton. His first patient was an 80-year-old woman who lost her nose to cancer.

When he presented the woman with her silicone nose prosthetic, Putnam watched as a weight lifted off her and her husband.

“I got to reintroduce a quality of life to that couple,” he said. “I found patients to be a much more appreciative audience.”

Over the next couple of years, Putnam honed his techniques using silicone before enrolling in a graduate school program for prosthetics at California State University, Dominguez Hills. He was older than most of his classmates, he said, but his experience as a professional sculptor gave him an advantage with his hand skills.

In 2007, Putnam began a residency in pediatric prosthetics at Scottish Rite. The hospital, originally founded to treat children with paralytic polio, is decked out in bright colors, artwork filled with crayons and fish tanks that look like scenes out of Finding Nemo.

More than 3,160 surgeries were performed at Scottish Rite in 2021, but the facility doesn’t particularly look, sound or smell like a hospital — a popcorn machine on the main floor floods the place with the scent of butter — which is an intentional decision made so patients feel safe and even excited for their visits.

It’s the perfect place for an artist like Putnam.

He knew within the first few weeks of working there that he wanted to stay at the hospital long term, so he built a niche making upper-extremity prosthetics using silicone.

“We recognized from the beginning that he had this extra skill of silicone prosthetics, and his ability to sculpt was just off the charts, as far as his artistic eye,” said Don Cummings, director of prosthetics at Scottish Rite.

Putnam said he’s found that people with upper-limb deficiencies, especially those who were born without a limb rather than losing it later in life, adapt fairly easily to everyday tasks without need for medical intervention. But some activities require extra tools.

Over the course of his prosthetics career, he’s made specialty parts as varied as those that can grip a violin bow or act like a springboard to allow a patient to compete in gymnastics. It’s a collaboration between the prosthetist and his patients to make a device that gives them additional freedom.

“Our motto at the hospital is giving children back their childhood, and that’s part of what he does. He addresses a specific need that a child has so that they can perform whatever activity it is they’re interested in,” Cummings said.

When Elena got her first prosthetic, it was almost immediately life-changing.

“It really is miraculous. You go from watching your child only crawl to, just within six days, being out on the playground and she was moving around,” Brittany Norman said. “Dwight gives her life. If she says ‘I want to do this,’ he figures out how to make that possible for her.”

A professional uncle

Creating a prosthetic limb is an arduous process consisting of little adjustments made over the course of a few weeks. It’s a dance Lucas Stockton knows well.

About once a month, the 14-year-old and his mom, Marissa, make the hour-and-10 minute drive from their home in Bridgeport to Putnam’s office for appointments to tinker with Lucas’ leg prosthetic.

Lucas was born without the lower half of his left leg, which was amputated by the umbilical cord while he was in the womb. He got his first prosthetic from Scottish Rite when he was 15 months old.

“It’s never been something I’ve struggled with,” Lucas said. “I’d be more confused if I woke up one day with both legs.”

The prosthetic, made of a top that slides over his thigh and a metal rod that serves as the lower part of his leg, has to adjust as Lucas grows, hence the frequent visits. Putnam can extend the bottom half of the device as Lucas gets taller, and every year or so the high school freshman gets outfitted for a new leg.

Making sure a prosthetic matches the exact needs of each individual is critical, especially for people using lower-limb prosthetics, said Elliot Rouse, director of the neurobionics lab at the University of Michigan.

“Legs support the body, so that puts them in a different regime in terms of risk compared to upper limb prosthesis,” Rouse said.

Pediatric prosthetists have to be cognizant of how much more physical children tend to be than adults.

“It has to be able to be rugged enough to withstand a kid’s lifestyle,” Putnam said. “A lot of times with adults, they’re going to get about a five year lifespan out of a prosthesis, whereas kids only get about 15 months for a leg and probably a year out of an arm, just based on growth and use.”

Prosthetics can be pricey, costing up to $25,000 or $30,000 for the most intricate devices. Insurance typically covers lower-extremity prosthetics, but coverage for an upper-extremity piece is more likely to get denied because insurers consider many activities to be easier to navigate without an arm than without a leg, Putnam said.

Scottish Rite provides financial assistance to qualifying families through their program Crayon Care, which covers either part of or the entire cost of care. Any family can apply for assistance through the program, regardless of income level or insurance.

Each of Lucas’ prosthetics — he’s had 12 so far — serves as a snapshot of who he was at that point in his life. He decorated his early devices with characters from his favorite shows, like Thomas the Tank Engine and SpongeBob SquarePants. His current leg has a subtle wood paneling pattern under stickers from bands and vacation spots.

Making prosthetics their own can be an important way for patients to feel involved in their health care. Norman, who is in the process of getting a new sport leg, chose a sea turtle design, although she’s already eyeing a Harry Potter-themed pattern for her next device.

While routinely visiting a hospital as a child could be a nuisance at best and scary at worst, Lucas said he feels comfortable at Scottish Rite, especially because he gets to visit with Putnam, whom he calls “Dr. Dwight.”

“It’s become routine,” Marissa Stockton said as she pulled up a photo on her phone of her son and Putnam hugging at an appointment eight years ago.

The prosthetist is a constant in his patients’ lives. After seeing Putnam for eight years, Elena even said she considers him “her best friend.”

“I become part of their extended family,” Putnam said. “It’s like I’m a professional uncle.”

Putnam gets a unique front-row seat to watch some of his patients grow up and develop their personalities.

Lucas has taken to writing and drawing. Other patients have found their passion in sports, including one cheerleader who invited Putnam to one of her games so he could see the prosthetic he created in action.

“It’s inspiring,” he said. “They show their thankfulness by going out and being kids.”